Primrose Saungweme still recalls the great sense of relief she felt when her baby was vaccinated at Chikanga Polyclinic in Zimbabwe last year.

“I felt so happy after he was vaccinated against polio,” says the 30-year-old mother of two who lives in Mountain Rise, a high-density suburb in the city of Mutare.

“I was worried because I heard stories of other children dying from polio and measles. After vaccination, I knew my baby was safe.”

Today she has returned with her bouncing baby boy Akundwe Mutiche, now 18 months old, for a routine check-up at the clinic.

Vaccines require continual power for storage

Chikanga Polyclinic uses power from solar energy stored in lithium batteries as a backup when there is load shedding or a power outage from the national grid.

With Zimbabwe and neighbouring countries in the grip of an energy crisis, these scheduled blackouts — where the power supply can’t keep up with demand — have become regular and prolonged.

But the batteries are helping to keep vaccines cool in the clinic’s cold storage.

Late last year, southern African nations had an outbreak of wild polio, threatening the lives of millions of children.

In late October, Zimbabwe embarked on a programme to vaccinate more than 2.5 million children under five years of age across the country to mitigate the deadly disease.

The country was already struggling to contain a measles outbreak since the first case reported in April 2022 in Manicaland Province. The disease went on to claim the lives of more than 750 people by early October 2022 and the government stopped publishing death figures so as not to “cause panic” among the citizens.

It rolled out a vaccination programme, and by October last year, around 85 percent of all children under five were fully vaccinated against measles nationwide.

The vast majority of vaccines should be stored at between 2°C to 8°C while the ideal temperature for a vaccine fridge is 5°C, according to the UK’s NHS.

With load shedding being experienced in Zimbabwe, keeping vaccines at the required cold temperatures at some of Zimbabwe’s clinics can be a menace for health workers.

How are solar stations helping?

Chikanga Polyclinic is one of the health facilities where solar stations were installed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in partnership with the Health Ministry.

Statistics from UNDP show that the ‘Solar for Health’ initiative has seen 1,044 health facilities powered by solar energy since its launch in 2016.

“The solar systems are 5 kilowatts (kW), 7kW, 10kW or 40kW, depending on the size of the facility and energy requirements to power specific functions like general lighting, laboratory, pharmaceutical cold chain, and pharmacy,” says UNDP spokesperson Anesu Freddy.

An official from the City of Mutare, the local authority in charge of Chikanga Polyclinic, tells Euronews Green that the solar system at the health facility is critical in providing uninterrupted power during load shedding.

“The system helps in vaccine storage and maintaining the cold chain,” he says, which covers everything from cold rooms to fridges and carrier boxes.

“It is also vital in Electronic Patient Management Systems and Electronic Health Records. Electronic data capturing is made easier and there is continued lighting even during load shedding, especially during the rainy season.”

Zimbabwe has been hit by a power crisis

In November, authorities in Zimbabwe were ordered to shut down Kariba, the country’s main power generation plant, until January. This was due to low water levels at the Kariba Dam, driven by climate change.

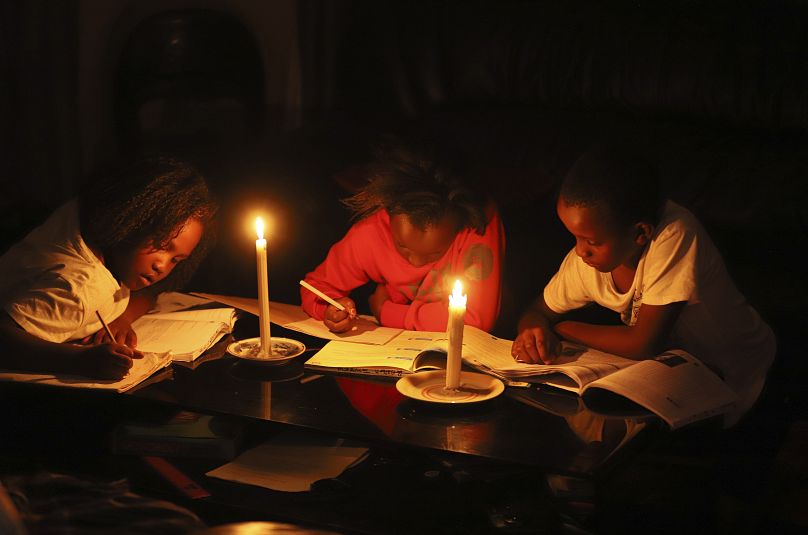

As a result, Zimbabwe imposed a more than 18-hour load-shedding schedule while in Zambia, people are going for 15 hours without electricity.

Zimbabwe needs an average power demand of about 1,735 megawatts (MW), according to the state-owned Zimbabwe Electricity Distribution Company (ZETDC).

As of 12 January, Zimbabwe’s available total electricity was at 695MW with the Kariba power plant generating 259MW below its installed capacity of 1,050MW. Hwange coal-fired power plant is producing 436MW.

To fill the power deficit, the country imports between 200MW and 450MW from its neighbours. These include South Africa’s state-owned electricity company Eskom Holdings, Mozambique’s Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa (HCB) and Zambia-owned power company Zambia Electricity Supply Corporation Limited.

Eskom, which usually bails Zimbabwe out, is also struggling to contain rolling blackouts at home. South Africa, the continent’s largest economy, is implementing a more than six-hour load shedding.

All hospitals in Zimbabwe could be boosted by solar power

“The government of Zimbabwe should urgently invest more in solar energy in our clinics, as solar energy is more reliable and sustainable especially given the current power crisis affecting the country,” says Itai Rusike, an executive director at Community Working Group on Health. The community-led organisation champions people’s right to equitable health services in the country.

“Solar energy is more efficient for the rural health centres and the hard-to-reach communities where power cuts are more frequent, as solar energy assists with the vaccine cold chain management and cold storage facilities in order to maintain vaccine integrity and avoid vaccine wastage.”

He says that the government should team up with development partners, non-governmental organisations and the private sector to strengthen health delivery services and improve the quality of health care by investing in solar energy in clinics.

“Community participation and community ownership in the health sector is also important as communities can assist in providing security and protecting the solar installations to avoid thefts and disruptions to health care services,” he explains.

Freddy points out that the solar installation project is being expanded to 19 additional health facilities in Zimbabwe from 2022 to 2023.

He says the UNDP is supporting the Health Ministry to mobilise resources to install solar systems at all public clinics and hospitals in the country.

Saungweme adds she is glad that she does not face any delays when she comes for a routine check-up with her baby at Chikanga Polyclinic.

“Back home we spend the whole day without electricity but here the nurses have never told us that they cannot treat my baby because of power shortages,” she says smiling while holding her baby.

“Electricity is always available here.”