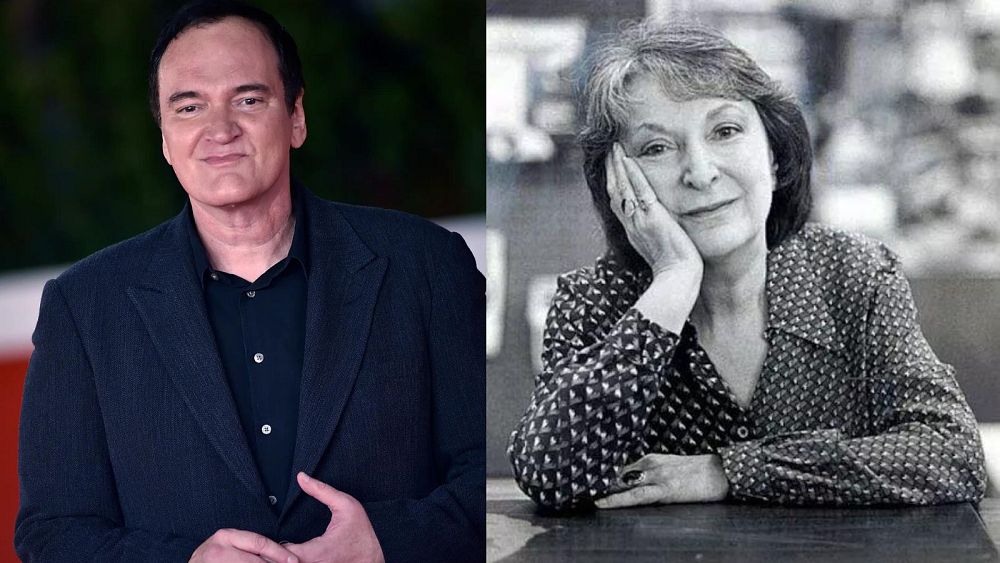

Quentin Tarantino’s 10th film, which the director has long said will be his final feature, will be called The Movie Critic.

According to The Hollywood Reporter, that is the name of the script that Tarantino has written and is set to direct this fall.

Any further details are top secret right now – probably locked in the 666-combination locked suitcase from Pulp Fiction – but sources describe the story as being set in late 1970s Los Angeles with a female lead at its center.

Of course, The Movie Critic is a working title and not final, so don’t be surprised if it doesn’t stick. However, it is a decent indication as to where the film may be headed… It is possible that the film could be based on the life of noted film critic Pauline Kael.

For years, the Oscar winning director has expressed interest and admiration for Kael, one of the most influential movie critics of all time. In a 1994 Time Magazine article, he stated that “she was as influential as any director was in helping me develop my aesthetic. I never went to film school, but she was the professor in the film school of my mind.”

Kael, who died in 2001, was not just a critic but also an essayist and novelist, known for her clashes with editors as well as filmmakers. The narrative’s timeframe seems to add up, adding further speculation that the firebrand critic will be the subject of Tarantino’s final film.

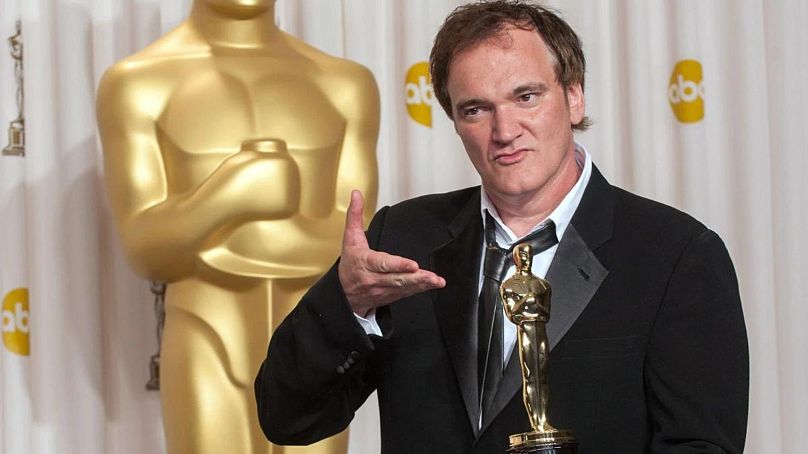

So far, Tarantino’s films have earned him countless awards, including the Palme d’Or for Pulp Fiction; four Golden Globes for Pulp Fiction (Best Screenplay), Django Unchained (Best Screenplay) and Once Upon A Time In Hollywood (Best Screenplay and Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy); two BAFTAs for Pulp Fiction and Django Unchained (both Best Original Screenplay); and two Oscars for Pulp Fiction and Django Unchained (Best Original Screenplay on both counts).

He’s also racked up three Best Director Oscar nominations (Pulp Fiction, Inglorious Basterds and Once Upon A Time In Hollywood) and one Best Picture nomination (Once Upon A Time In Hollywood) but failed to win either coveted prize.

You can bet that considering The Movie Critic will be his supposed last film, he’ll ache to remedy this and go out on a golden bang…

Why is Tarantino quitting after 10 films?

Tarantino has long maintained his desire to go out at the top of his game and has frequently said he’d bow out after 10 films and retire by the time he is 60.

His rationale is that even the most celebrated directors see their quality of work diminish later on in life, and he wants his filmography to be remembered “without a misfire”.

In 2012, he told Playboy: “I want to stop at a certain point. Directors don’t get better as they get older. Usually the worst films in their filmography are those last four at the end. I am all about my filmography, and one bad film f**ks up three good ones. I don’t want that bad, out-of-touch comedy in my filmography, the movie that makes people think, ‘Oh man, he still thinks it’s 20 years ago.’ When directors get out-of-date, it’s not pretty.”

Fair enough, but technically, he’ll miss out on both his statements, as Tarantino turns 60 this month (on 27 March, in case you were thinking of sending a card).

That and if we’re being strict about his methodology, he’s already directed 10 films:

-

Reservoir Dogs — 1992

-

Pulp Fiction — 1994

-

Jackie Brown — 1997

-

Kill Bill: Volume 1 — 2003

-

Kill Bill: Volume 2 — 2004

-

Grindhouse: Death Proof — 2007

-

Inglorious Basterds — 2009

-

Django Unchained — 2012

-

The Hateful Eight — 2015

-

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood — 2019

Yep, that’s 10 films already, but Tarantino considers the two Kill Bill movies as one. Audiences still had to pay for two separate cinema tickets for each film though, so let’s not fool ourselves — The Movie Critic will be his 11th film.

But whatever helps Quentin sleep at night…

And for those already dreading a cinematic landscape without the film history-obsessed writer-director who has built a reputation on celebrating and reviving so-called “fringe” genres, fear not. Tarantino has expressed interest in other creative outlets, noting in interviews that he could direct limited series or plays. In 2021, he published his first novel, a novelization of Once Upon A Time In Hollywood, and while promoting his 2022 book “Cinema Speculation,” Tarantino revealed plans to shoot an eight-episode television series.

Who was Pauline Kael?

Pauline Kael (1919 – 2001) was an avid movie fan and remains film criticism royalty. She was the most influential film critic of her era, a passionate cultural critic who was never shy of telling it straight.

She published her first piece of film criticism in 1953 in City Lights magazine in San Francisco. Other articles followed in Partisan Review, Moviegoer and other journals, and her work began to appear regularly in Film Quarterly.

For several years from 1955 she broadcast film reviews over the radio stations of the Pacifica network.

Her reputation grew for her raw, lively and acerbic takes, and a collection of her articles was published in 1965 under the title «I Lost It at the Movies». The book was a best-seller and won her assignments from major magazines as Life, Holiday, Mademoiselle, and McCall’s.

She joined The New Yorker in 1968 and reviewed films for them until her retirement in 1991.

Here are some of her most memorable takes:

On Bonnie And Clyde:

“‘Bonnie and Clyde’ is the most excitingly American American movie since ‘The Manchurian Candidate’ (…) The audience is alive to it. Our experience as we watch it has some connection with the way we reacted to movies in childhood: with how we came to love them and to feel they were ours — not an art that we learned over the years to appreciate but simply and immediately ours.”

From “Trash, Art, and the Movies”:

“A good movie can take you out of your dull funk and the hopelessness that so often goes with slipping into a theatre; a good movie can make you feel alive again, in contact, not just lost in another city. Good movies make you care, make you believe in possibilities again. If somewhere in the Hollywood-entertainment world someone has managed to break through with something that speaks to you, then it isn’t all corruption. The movie doesn’t have to be great; it can be stupid and empty and you can still have the joy of a good performance, or the joy in just a good line. An actor’s scowl, a small subversive gesture, a dirty remark that someone tosses off with a mock-innocent face, and the world makes a little bit of sense. Sitting there alone or painfully alone because those with you do not react as you do, you know there must be others perhaps in this very theatre or in this city, surely in other theatres in other cities, now, in the past or future, who react as you do. And because movies are the most total and encompassing art form we have, these reactions can seem the most personal and, maybe the most important, imaginable.”

From “Stanley Strangelove: A Clockwork Orange”:

“The movie’s confusing — and, finally, corrupt — morality is not, however, what makes it such an abhorrent viewing experience. It is offensive long before one perceives where it is heading, because it has no shadings. Kubrick, a director with an arctic spirit, is determined to be pornographic, and he has no talent for it. In Los Olvidados, Buñuel showed teen-agers committing horrible brutalities, and even though you had no illusions about their victims — one, in particular, was a foul old lecher — you were appalled. Buñuel makes you understand the pornography of brutality: the pornography is in what human beings are capable of doing to other human beings. Kubrick has always been one of the least sensual and least erotic of directors, and his attempts here at phallic humour are like a professor’s lead balloons. He tries to work up kicky violent scenes, carefully estranging you from the victims so that you can enjoy the rapes and beatings. But I think one is more likely to feel cold antipathy toward the movie than horror at the violence — or enjoyment of it, either.”

On It’s a Wonderful Life:

“Frank Capra’s most relentless lump-in-the-throat movie … In its own slurpy, bittersweet way, the picture is well done. But it is fairly humourless and, what with all the hero’s virtuous suffering, didn’t catch on with the public. Capra takes a serious tone here, though there’s no basis for the seriousness; this is doggerel trying to pass as art.”

On Chloe in the Afternoon:

“Eric Rohmer’s ‘Chloe in the Afternoon,’ which opened the New York Film Festival, will probably be called a perfect film, and in a way I suppose it is, but it had evaporated a half hour after I saw it. It’s about as forgettable as a movie can be. Maybe Rohmer, who has become a specialist in the eroticism of non-sexual affairs, has diddled over a small idea too long; perhaps intentionally (but who can be sure?), this is a reductio ad absurdum. The will-he-or-won’t-he game (an intellectualized version of the plight of Broadway virgins) goes on so long that the squeamish hero must be meant to be an ass.”

From “Fear of Movies”:

Discriminating moviegoers want the placidity of nice art—of movies tamed so that they are no more arousing than what used to be called polite theatre… This is, of course, a rejection of the particular greatness of movies: their power to affect us on so many sensory levels that we become emotionally accessible, in spite of our thinking selves. Movies get around our cleverness and our wariness; that’s what used to draw us to the picture show. Movies—and they don’t even have to be first-rate, much less great—can invade our sensibilities in the way that Dickens did when we were children, and later, perhaps, George Eliot and Dostoevski, and later still, perhaps, Dickens again. They can go down even deeper—to the primitive levels on which we experience fairy tales. And if people resist this invasion by going only to movies that they’ve been assured have nothing upsetting in them, they’re not showing higher, more refined taste; they’re just acting out of fear, masked as taste. If you’re afraid of movies that excite your senses, you’re afraid of movies.”

From «Kiss Kiss Bang Bang: Film Writings, 1965-1967»:

“When the bespangled Miss Charisse wraps her phenomenal legs around (Fred) Astaire, she can be forgiven everything — even the fact that she reads her lines as if she learned them phonetically.”

If you want to know more about Pauline Kael, you could do a lot worse than to seek out What She Said: The Art of Pauline Kael, Rob Garver’s 2018 documentary which offers the portrait of the work and life of the film critic and her battle to achieve success and influence in the 20th century movie business.